Multiple blue screens of death, caused by an update pushed by CrowdStrike, on airport luggage conveyer belts at LaGuardia Airport, New York City. Smishra1, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Unless you've been hiding under a rock or seriously been off-grid in in the last week, you will have seen the near continuous news coverage of the global IT outage caused by a defective release of CrowdStrike content. Unfortunately even reasonably trustworthy news sources misunderstand the issue. Worse still are the numerous industry professionals that are quick to declare the root cause of the issue - in complete contradiction to CrowdStrike's statements. The worst of all are some of CrowdStrike's competitors that are saying that this would have never happened to them and even offering to switch customers over. This ambulance chasing is frankly disingenuous and insulting to all seasoned cybersecurity professionals.

So let's dispel the myths and disinformation and objectively consider the situation.

Disclaimer: Caribbean Solutions Lab is both an independent CrowdStrike customer and partner. Being independent indicates that we pay for our licenses just like any other customer. And CrowdStrike is just one of several tools we use to protect our endpoints.

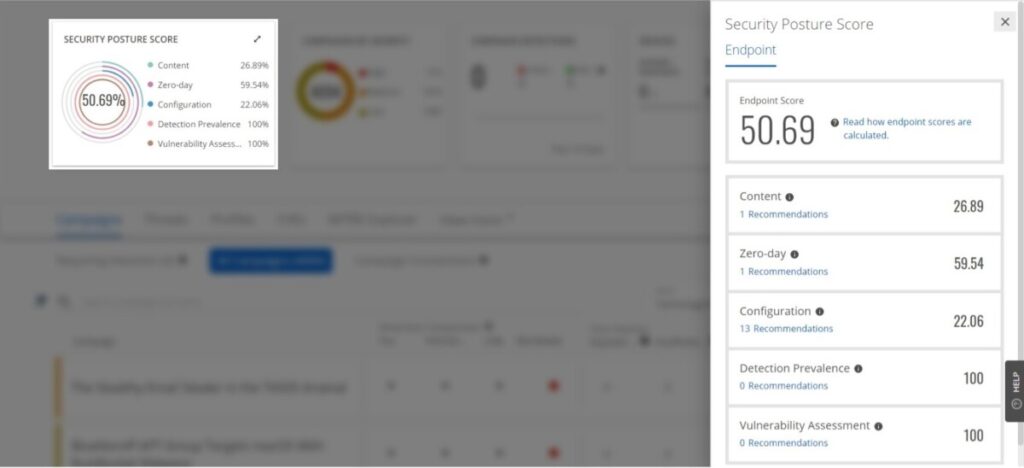

What is CrowdStrike? CrowdStrike the cybersecurity company was founded in 2011 by George Kurtz, Dimitri Alperovitch, and Gregg Marston. George and Dimitri were previously at McAfee, in fact George was McAfee's CTO (more on this fact later). CrowdStrike started out as an Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) tool but has grown into a cybersecurity platform that as of 2024 commands an impressive ~25% market share of the global endpoint protection market. Their core product is the Falcon sensor, an application that is installed on endpoint systems (e.g. Windows, Linux, MacOS) and that detects and responds to threats. In order to protect the underlying operating system, Falcon must operate in what is commonly called privileged mode and have full access to the operating system's kernel or core. For Microsoft Windows, this is by design and a convention enables all antivirus and endpoint protection (AV/EP) products operate.

What happened? Based upon CrowdStrike disclosures, on Friday, 19 July 2024, CrowdStrike released a routine content update, Channel File 291. Organizations in Australia were the first to start experiencing systemic crashes evidenced by Windows blue screens of death (BSoD). By the time the Americas had started their Friday, the problem was documented to have affected millions of CrowdStrike installations in Europe as well. In hindsight, we know that Microsoft Windows systems were affected, not Linux or MacOS systems. Within hours of discovering the issue and despite published remedations, the damage had been done to any systems that were online and able to download the offending content file. Systems that did not download the problem file were not affected. We fell into this group, having had all of our systems offline overnight - as we're 100% cloud-based. The resolution is to simply boot into safe mode, and remove the offending files, reboot and then allow CrowdStrike Falcon to download a working version.

How hard can it be? On paper this is a straightforward process, but the actual process isn't trivial due to everything from encrypted hard drives, to virtual and remote systems. Even a nominal 15 minute recovery time, factored for 8.5 million devices equates to at least two million man hours. For anyone that has been in the industry long enough, you know that recovering Microsoft Windows is never as clean in practice as it is on paper. First you have to successfully boot into safe mode. There are documented cases where this must be attempted 15 times before successful and then being able to remove the bad CrowdStrike file. For encrypted systems, recovery keys need to be provided in order to decrypt the hard drive and access the system. On large systems, booting can sometimes take several minutes under perfect conditions, which these are not. CrowdStrike has provided guidance and toold to help organizations automate the recovery process. Microsoft, having a vested interest in recovery of their mutual customers has also released guidance and tools. In fact many industry professionals, other IT companies, and service providers have jumped in to help. Given the exceptionally wide blast radius of this event, the entire industry (mostly) has been working towards speedy recovery. Unfortunately threat actors have also been quick to take advantage of the news cycle and have been actively campaigning with fake information and fixes.

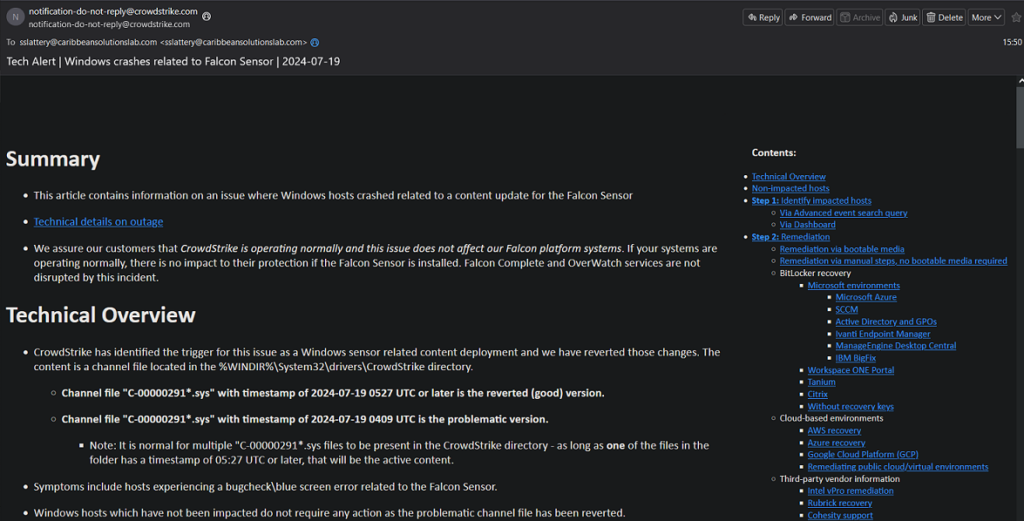

What has gone well? CrowdStrike has been very transparent about the issue and communicating with customers. I have seen some of George's interviews and unfortunately the journalists lack of understand isn't helping matters. Emails such as the screenshot below have been forthcoming several times a day. As of 22 July 2024, CrowdStrike indicates that a significant number of systems are back online, but realistically it may be weeks before full recovery.

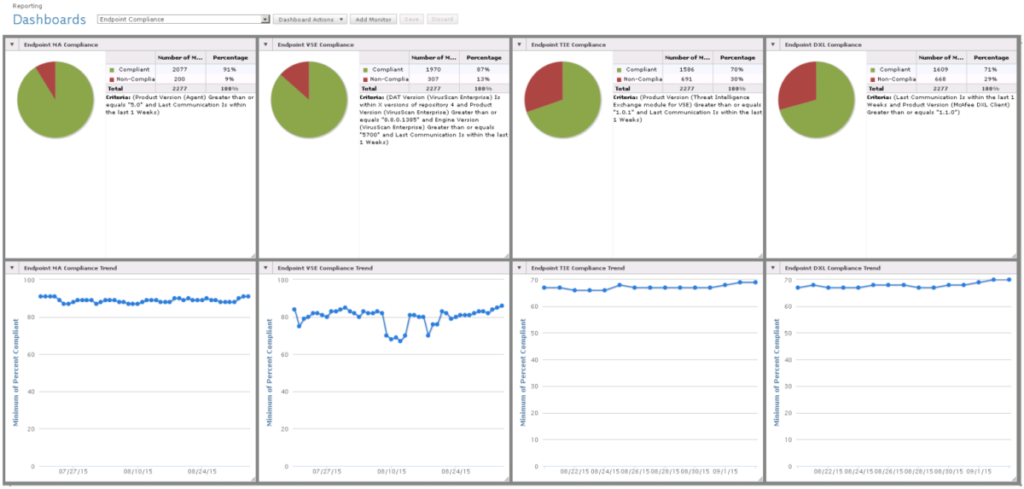

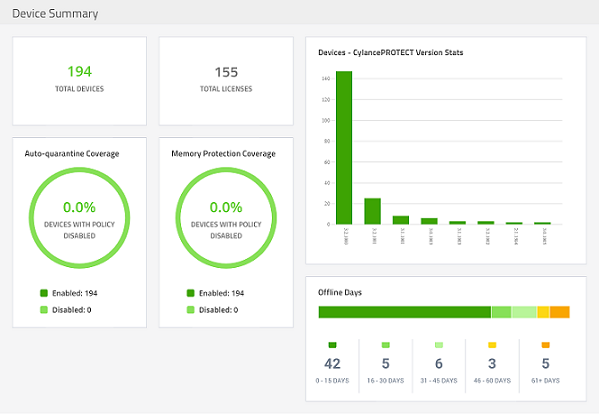

What really went wrong? Depending upon how much CrowdStrike eventually makes public, we may never really know. But lets be clear about a few things. First, the problematic file was a content update and NOT a patch or application update - which many supposed pundits and competitors say. The challenge for all security vendors is to provide protection to customers while keeping up with onslaught of threats. Current estimates are that there are over 500 million new and unique pieces of malware generated every day. So how to you get the latest instructions (content/signatures/DAT files) on how to detect threats to endpoints in a timely manner? Transferring a file is the oldest and most common technique and used by CrowdStrike and hundreds of other endpoint security vendors. Another method is to use web-based or online content, negating the need to transfer files but requiring a constant Internet connection. A less common method is to build the content into the application itself. This method is currently used by Microsoft Windows' native Defender product but is a more onerous process and problematic for structured management and change control. Then there is the completely signatureless route where the endpoint protection doesn't need regular updates or to be online. Cylance PROTECT (now owned by Blackberry) is a prime example of this approach. Some vendors such as McAfee use a hybrid approach combining a very modular architecture with regular content updates, online content, periodic engine upgrades. Speaking of McAfee, in 2010 a bad McAfee content file (5958 - yes I was there) instructed its AV to consider a key windows process (SVCHOST) malicious and triggered deletion. The negative effects were global and widespread, though not quite as wide as CrowdStrike today. McAfee's then CEO, Dave Dewalt and George's boss, publicly acknowledged fault, apologized and promised to do better. Some of McAfee's current content distribution architecture were developed from that incident. There are no right or wrong approaches to delivering the necessary threat intelligence to deployments. There are pros and cons to each.

Were mistakes made? Maybe, but time will tell. Until proven otherwise I am confident that CrowdStrike does take reasonable efforts to test before release. But given the practically infinite number of combination of versions and languages of operating systems, applications, hardware, device enabling drivers, it is impossible to test every scenario. For those saying that this can't happen with their product or tool, they are basically saying a mistake will never be made. If that were really the case why do they ever need to update or patch their product? Couldn't they get it 100% correct the first time and never have to change a thing? Of course not. Microsoft Windows alone changes every month on Patch Tuesday. Lather, rinse, and repeat for every other vendor and app present on a given system. It is certainly true that a non-signature based product can't have a problem with a signature, but does it really matter to you and I as consumers, what part of an application or system is faulty? Some pundits argue that staged deployments and testing are ways to avoid global outages. It has already disclosed that the outages followed Friday's rising sun. Some of that might just be because of who was awake to witness the outage. But CrowdStrike is a global 24x7x365 operation and not just tied to western hemisphere time zones so they were surely gathering data as the issues started to be documented.

What could be done better? CrowdStrike currently does not expose management of content updates and distribution. Enabling staging with a kill switch in case of emergency would be useful and seems like something easily implemented. I also expect CrowdStrike to review and tweak their procedures to reduce the risk of a similar future incident. Microsoft could certainly improve Windows' recovery procedures and architecturally Microsoft could learn a few things on kernel protection from the likes of Apple MacOS.

What can you do? Plan for failure. Sooner or later, whether due to an application fault, hardware issue or something external like a hurricane or cyber attack, things will break. Similar scenarios have happened before with McAfee, Kaspersky, Symantec, and even Microsoft. Test and practice your recovery procedures. In terms of cybersecurity, some advocate for hedging bets and running different AV/EP products. If you can afford this approach why not? But how would this work? Running one product for servers and one for workstations (a very simplistic setup) doesn't really remove the concentration risk on critical infrastructure. So maybe you protect half of your systems with one product and the other half with another. This is great if your resources are evenly split but how many of you have two production versions of every server/role? I'm sure very few. Now consider a mildly complex organization. There isn't a clear, universal solution. So I refer you back to my first statement: Plan for and practice for failure.

Useful Links:

- CrowdStrike statement to customers and partners - https://www.crowdstrike.com/blog/to-our-customers-and-partners/

- CrowdStrike Remediation & Guidance Hub - https://www.crowdstrike.com/falcon-content-update-remediation-and-guidance-hub/

- Microsoft Blog : Helping our customers through the CrowdStrike outage - https://blogs.microsoft.com/blog/2024/07/20/helping-our-customers-through-the-crowdstrike-outage/

- Global Microsoft Meltdown Tied to Bad Crowdstrike Update - https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/07/global-microsoft-meltdown-tied-to-bad-crowstrike-update/

- CrowdStrike IT outage affected 8.5 million Windows devices, Microsoft says - https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cpe3zgznwjno